Born in January, 1949, in Malaya in the days before independence granted the vote and a penultimate ‘si’, I was brought up on a rubber plantation, strangely named ‘Seafield’, though ten miles inland, near the kampong of Puchong, or “Puddle” as we called it, along with my brother, a twelve inch Michelin rubber-tyre man, my parents, our Amah, the wonderful Siti, her son Kamal, 20 SC’s (Special Constables) and their sandbagged machine-gun post with searchlight, our mongrel, Riko, banana trees, a chicken run, home-made swimming-pool, ground-nuts, a 12ft high barb-wired compound and rubber trees as far as you could see.

It was the ‘Emergency’, that period when the Chinese allies that Britain had funded during WWII to hide out in the Malay jungles and attack the Japanese Imperialists invaders, turned against their benefactors and hid out in the Malay jungles and attacked the British Imperialist invaders. On the estates, ungrateful daytime ‘coolies’ became ‘bandits’ by night, slashing the trees they tended, but all the way round.

A faithful son of Empire, I returned to Great Britain to celebrate the Coronation of the young Elizabeth and join in the cheerful festivities from my high window, feasting on raw egg and ice cream. I, too, played my part, donating selflessly for the greater good, though I was never told why the Crown required my tonsils-and-adenoids.

To convalesce I was placed in a Devon boarding school to enjoy a seemingly endless quarantine after a child contracted polio there, while my parents toured the United Kingdom visiting relatives.

My reward for this sacrifice came on the return flight, in one of those new shiny state-of-the-art jet airliners, the Comet Four, for, as all the passengers slept and dreamed, I was invited to sit with the pilot in the cockpit and handle the controls as we clipped over the magical Himalayan peaks at the end of the day. Bliss. I would like to think I looked down on little Hillary and tiny Tensing waving back at me from their little peak, but sadly it could only have been that wee Jack they left behind, waving forlornly in the icy blast.

I climbed aboard one of these at Duxford air museum recently and was surprised at how it had shrunk over the years. I could barely stand up straight in the centre aisle!

Having seen the advantages of the boarding-school education at first hand, my parents packed me off, fully four and a half, to a school at the proper distance of 250 miles from a change of heart. We travelled by canvas-seated Dakota aeroplane and pencil-shaped Saracen armoured car, up and away from the sweaty jungles of my infancy to breathe the cool pure air of the Cameron Highlands. Here, again, I experienced the joy of being invited up into the ‘cockpit’ gun-turret and peer through its sights into the deepest recesses of the green jungle as my fellow passengers vomited their way to the top in the steel oven below.

My enduring memory of this school was of gazing in awe, for an instant, upon the grey-beige of my kneecap before it drowned in a flood of bright red and then at the culpable stone.

A year later, we were chauffeured, in our personal 1930’s American fast-backed armour-plated car with its driver’s visor-slit, to a beach-side barracks’ school at Port Dickson, commanded by the awesome figure of an ex-army major: “Drum-Tum!”

Discipline here was tough: morning lessons, interrupted only by a fresh coconut milk-and-crunchy break, were followed, after lunch, by swimming and sports on a sweeping white seemingly endless sandy beach. At one end, a small river trickled through a mangrove swamp into the azure ocean while at the other little sampans set out into the Malacca Straits from a fragrant Malay fishing kampong and returned with tiny ikan bilis and huge flat sting-rays flapping across the gunwales.

My enduring memory of this place was of being confined, in a delirium, in the doorless end bay of the barracks that was nominated the ‘sickroom,’ with its view of the coconut trees lining the land drain that bounded our property. Here I saw (as described by Charles Darwin in his Beagle record of 1836) “even a huge land crab… furnished by nature with a curious instinct and form of legs to open and feed upon the same fruit (the coconut)” advancing purposefully out of that great drain, across the few yards to the barrack’s door, and on towards my cot, ever larger, its clicking pincers agape, grinning at me.

It could climb, my delirium assured me, the leg of my little bed with ease and with equal ease split…

I was transferred to the main house and bedded on the first floor, next to the girls’ dorm for the remaining duration of my sickness, where I made my own Darwinian discovery of ‘species’ differentiation.’

(Next week: the boy from the colonies finds a place in English society)

Thursday, 12 February 2009

Sunday, 8 February 2009

A cave, a bone, a tooth and time.

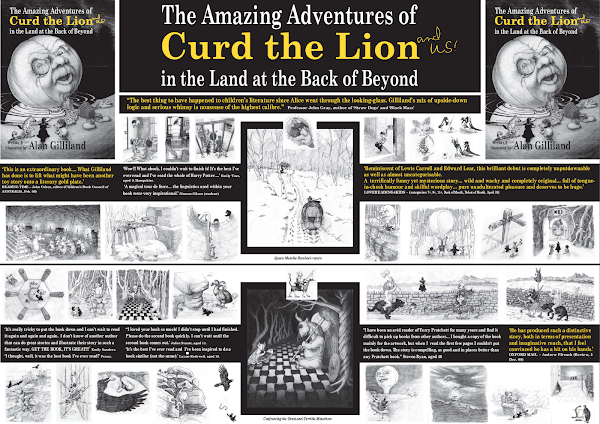

When I started out on this venture (writing my Curd the Lion book – see first post) years ago, a strangely parallel adventure befell us in real life.

I started writing and drawing the first pictures for this story of Curd the Lion and his friends, Pilgrim Crow, Sweeney the Heenie (hyena) and O’Flattery the Snake, when my fourth child, Oliver, was born.

Soon after this I took my eldest two children, Ben and Emily, on a picnic trip. Walking along the rocky bed of a half-dry stream winding through the woods, we noticed a small cliff.

Halfway up it we saw an enticing little cave with a ledge just right for a picnic. We climbed up and sat down to look at the view as we ate our sandwiches ( because children are always hungry), before exploring the cave.

The cave, we could see, went much deeper than we had expected and its lure gobbled up the sandwiches as fast as I could unwrap them.

We walked and stooped and crawled our way way into it as far as we could, discovering side tunnels and old stalactites and -mites and other bumps to bang your head and stub your toes.

Armed with my promise to return with torches and a ball of string (to find our way out again) we returned to the entrance. Scratting about in the mud looking for fossils, one of us picked up a very bone-shaped object. Picking off a little of the limestone coating we saw that it was indeed a bone.

The local museum curator confirmed that we had found, here in England, the metatarsal foot-bone of an hyena from before the last ice-age!

We were all very excited, given that Sweeney the Heenie, Curd’s rival in the story, was an hyena.

Six months later, just as I was finishing the first draft of the story, we returned, armed with hope, torches, string, trowels, a knife to scrape with and a bottle of water to rinse anything we found.

It wasn’t long before we unearthed an object that, upon scraping away the limestone coating, revealed itself to be a huge and pristine enameled tooth.

Of course, it could only be the tooth of a cave-lion just like Curd – a magical end to the story of my story-making.

We were only slightly disappointed when the Natural History Museum confirmed that BOTH foot-bone and tooth belonged to an hyena.

Only a year or two ago I discovered that our ‘secret’ cave was once famous.

Known as the ‘Hyena Cave’, discovered by quarrymen in the early 19th century, it contained a vast quantity of hyena bones, along with various other local Yorkshire creatures, such as elephants, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, bison, giant deer, small mammals and birds.

The study of these bones led eventually to a refutation of the then accepted view that the Great Flood of the Bible had either swept such creatures there (all the way from Africa) or drowned them in situ.

All the animal bones except those of the hyenas, were chewed and broken, and only partial. The cave, it appears, was a den occupied by hyenas for a very long time.

It was the cave that changed time! (from that of a consensual biblical to a scientific perception of pre-history).

Our metatarsal has since taken a walk (perhaps it’s on its way home to Yorkshire) but the great fang still keeps me company in my little shed in West Sussex.

I started writing and drawing the first pictures for this story of Curd the Lion and his friends, Pilgrim Crow, Sweeney the Heenie (hyena) and O’Flattery the Snake, when my fourth child, Oliver, was born.

Soon after this I took my eldest two children, Ben and Emily, on a picnic trip. Walking along the rocky bed of a half-dry stream winding through the woods, we noticed a small cliff.

Halfway up it we saw an enticing little cave with a ledge just right for a picnic. We climbed up and sat down to look at the view as we ate our sandwiches ( because children are always hungry), before exploring the cave.

The cave, we could see, went much deeper than we had expected and its lure gobbled up the sandwiches as fast as I could unwrap them.

We walked and stooped and crawled our way way into it as far as we could, discovering side tunnels and old stalactites and -mites and other bumps to bang your head and stub your toes.

Armed with my promise to return with torches and a ball of string (to find our way out again) we returned to the entrance. Scratting about in the mud looking for fossils, one of us picked up a very bone-shaped object. Picking off a little of the limestone coating we saw that it was indeed a bone.

The local museum curator confirmed that we had found, here in England, the metatarsal foot-bone of an hyena from before the last ice-age!

We were all very excited, given that Sweeney the Heenie, Curd’s rival in the story, was an hyena.

Six months later, just as I was finishing the first draft of the story, we returned, armed with hope, torches, string, trowels, a knife to scrape with and a bottle of water to rinse anything we found.

It wasn’t long before we unearthed an object that, upon scraping away the limestone coating, revealed itself to be a huge and pristine enameled tooth.

Of course, it could only be the tooth of a cave-lion just like Curd – a magical end to the story of my story-making.

We were only slightly disappointed when the Natural History Museum confirmed that BOTH foot-bone and tooth belonged to an hyena.

Only a year or two ago I discovered that our ‘secret’ cave was once famous.

Known as the ‘Hyena Cave’, discovered by quarrymen in the early 19th century, it contained a vast quantity of hyena bones, along with various other local Yorkshire creatures, such as elephants, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, bison, giant deer, small mammals and birds.

The study of these bones led eventually to a refutation of the then accepted view that the Great Flood of the Bible had either swept such creatures there (all the way from Africa) or drowned them in situ.

All the animal bones except those of the hyenas, were chewed and broken, and only partial. The cave, it appears, was a den occupied by hyenas for a very long time.

It was the cave that changed time! (from that of a consensual biblical to a scientific perception of pre-history).

Our metatarsal has since taken a walk (perhaps it’s on its way home to Yorkshire) but the great fang still keeps me company in my little shed in West Sussex.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)