I was rudely inducted into the native (as opposed to colonial) English way of life when, having arrived after a six-week voyage round the Cape of Good Hope (Suez Crisis) with my tan wan from Yellow Fever, post-recovery I was packed off to another boarding school near Battle, East Sussex.

Here I discovered, among other things, the meaning of the cane and the other use for the cricket bat, before settling into a routine of overt compliance with the many regulations that ensure the smooth running of an hundred or more boys.

Loyalty to one’s ‘House’ was instilled by naming them after the warring city-tribes of ancient Greece and tested on the playing fields below. I was a Corinthian, blue, and certainly more elevated (we had our own columns, after all) than the warlike Spartans (red) or wet Athenians (green).

Naturally, we learned Greek as well as Latin, the better to learn English and for the sheer discipline, through good offices of our Latin, and Head-, Master, the redoubtable Mr. “Shere” Kahn (correct – not Khan) and a well-aimed chalk or board rubber.

There the obligatory midnight feasts under the floorboards of the gym were hosted by those Epicurians whose fathers smuggled bottled chicken and pickles in the boots of their Bentleys to instil in their offspring early the art of entrepreneurial domination through largesse and favouritism. In the weekly tuck-shop grab we all queued eagerly craning our necks to see as our lockers containing a half-term’s supply were opened, one by one, under the eagle eye of the moustachioed Matron Crabtree, and their rationed treasures extracted, followed by the inevitable bartering sessions in which we discovered the relative value of different confections and altered our holiday orders to secure the maximum exchange-rate-benefits the following term.

Whether officially sanctioned or not, I fail to remember, but we boys brought to school mementoes of our, or other, former lives and other cultural treasures, for many and varied were our origins. My collection included World War One German field-glasses (later cunningly disassembled by my brother to access the lenses and prisms), my grandfather’s World War One brass army compass, a parang (Malay jungle knife), Kukri (Ghurka knife), Kris (Malay ceremonial execution knife) and a jungle saw (two loops and a sawed wire which one tensed across a knotched stick bent over like a bow) to complete the ‘jungle-shelter’ building equipment for use on ‘frees’ deep in the four hundred acre woods. But my pride was the six-foot long Semang (or Sakai, I forget which of the indigenous peoples gave this to my father) blowpipe with its bamboo darts that could penetrate solid wood.

Our inspirational Maths master, the (seemly) eighty-year-old Colonel “Pepperpot” Pearson, with his shiny freckled pate and white Nietzschean moustache tinged with tobacco-juices, and his “have a Mintoe, boy” response to every correct answer, could often be seen out of school hours galloping full pelt across field and hedge on his huge cavalry charger.

I learned to run (faster), to play rugger (rougher), and cricket (harder) and I was all set on a career as a leg spin bowler (tested by bowling onto an hand-kerchief, moved ever further from the stumps) for the second eleven when an unfortunate accident put paid to my joining the lower ranks of that elite band of demi-gods, the sporting heroes.

It was the Easter of my final year there when a group of doughty lads set out to climb a local chalk quarry under the vigilant gaze of my neighbour, a doctor. (Easter and accidents go together in my life: apart from this accident, it was Easter when, after leaving the Daily Telegraph, I collapsed with a catastrophic bacterial spinal infection; it was Easter when my unfortunate mother conceived a baby who shocked her, after being extracted with a pair of tongs, with its tadpole-like long body and large head, flat on one side, a facet explained away by the doctor as merely a consequence of my cork-like extraction.)

I succeeded in climbing the walls of this quarry and descending again first. I was busy minding my own business, gloating at my prowess, some ten feet away from and with my back to the base of the cliff while watching the barbecue preparations and waiting for the sluggard above to complete his ascent, when, as if reading my thoughts, the swine triggered an avalanche of pebbles skittering down the face.

One particularly large and athletic rock outleaped his fellows and bounced, with a dull squelch, upon my skulltop. I watched him leap away in triumph as I felt a slick stickiness where my smooth hair used to be, followed by trickling sensation down my left temple and a queer heaving sensation in my stomach.

Walking slowly, whether casually or groggily I don’t remember, over to the doctor in charge, I unnecessarily showed him my bloody hand. Taking stock of the wound, he took out a pocket-handkerchief (before tissues became common), laid it upon my head and tied it gently under my chin.

In this disguise (a Russian peasant-girl) I sat and waited patiently in the car as the barbecue party got under way, ran its course, sputtered out and packed itself away, kicking out its embers some three hours later. I sat and waited as our troop drove happily home. I sat and waited as the doctor’s mother made to swab my cut before sending me across the fence, home.

My sudden attempt to disappear under the kitchen table alerted the doctor to new possibilities in my wound and we set off for the local hospital, 15 miles away, for an x-ray. My being sick all over the dashboard confirmed his tentative diagnosis, and I passed through the x-ray room straight into an ambulance for the fifty-mile dash to the Atkinson-Morley Head hospital in Wimbledon.

I arrived just in time to wave hello to Stirling Moss, who beat me to Casualty by minutes after his big Easter crash at Goodwood, and goodbye to my blood, most of which seemed to have deserted me, prefering the starched white covers of the ambulance bed.

My next memory of this Easter was that of the voice of a swarthy matron, “Be quiet! Stop making such a fuss. You’re disturbing the other patients.” After drifting between coma and complaint for several m and sucking hot Bovril through a straw while laid on my good side, it was finally time for a dressing change.

Whimpering as she unbuckled the nappy-pin with which my voluminous head-bandages were fastened, I selfish made more noise as she placed her hand on my head and tugged, drawing the hefty pin through the layers of bandages sandwiching my right ear. With the sudden flowering of that pink rose it dawned on her that she had been forcing me to sleep on my pierced ear!

(next week - more boarding, more boredom)

Friday, 20 February 2009

Thursday, 12 February 2009

Potted Biog Blog: part one –the Tropic of Capricorn

Born in January, 1949, in Malaya in the days before independence granted the vote and a penultimate ‘si’, I was brought up on a rubber plantation, strangely named ‘Seafield’, though ten miles inland, near the kampong of Puchong, or “Puddle” as we called it, along with my brother, a twelve inch Michelin rubber-tyre man, my parents, our Amah, the wonderful Siti, her son Kamal, 20 SC’s (Special Constables) and their sandbagged machine-gun post with searchlight, our mongrel, Riko, banana trees, a chicken run, home-made swimming-pool, ground-nuts, a 12ft high barb-wired compound and rubber trees as far as you could see.

It was the ‘Emergency’, that period when the Chinese allies that Britain had funded during WWII to hide out in the Malay jungles and attack the Japanese Imperialists invaders, turned against their benefactors and hid out in the Malay jungles and attacked the British Imperialist invaders. On the estates, ungrateful daytime ‘coolies’ became ‘bandits’ by night, slashing the trees they tended, but all the way round.

A faithful son of Empire, I returned to Great Britain to celebrate the Coronation of the young Elizabeth and join in the cheerful festivities from my high window, feasting on raw egg and ice cream. I, too, played my part, donating selflessly for the greater good, though I was never told why the Crown required my tonsils-and-adenoids.

To convalesce I was placed in a Devon boarding school to enjoy a seemingly endless quarantine after a child contracted polio there, while my parents toured the United Kingdom visiting relatives.

My reward for this sacrifice came on the return flight, in one of those new shiny state-of-the-art jet airliners, the Comet Four, for, as all the passengers slept and dreamed, I was invited to sit with the pilot in the cockpit and handle the controls as we clipped over the magical Himalayan peaks at the end of the day. Bliss. I would like to think I looked down on little Hillary and tiny Tensing waving back at me from their little peak, but sadly it could only have been that wee Jack they left behind, waving forlornly in the icy blast.

I climbed aboard one of these at Duxford air museum recently and was surprised at how it had shrunk over the years. I could barely stand up straight in the centre aisle!

Having seen the advantages of the boarding-school education at first hand, my parents packed me off, fully four and a half, to a school at the proper distance of 250 miles from a change of heart. We travelled by canvas-seated Dakota aeroplane and pencil-shaped Saracen armoured car, up and away from the sweaty jungles of my infancy to breathe the cool pure air of the Cameron Highlands. Here, again, I experienced the joy of being invited up into the ‘cockpit’ gun-turret and peer through its sights into the deepest recesses of the green jungle as my fellow passengers vomited their way to the top in the steel oven below.

My enduring memory of this school was of gazing in awe, for an instant, upon the grey-beige of my kneecap before it drowned in a flood of bright red and then at the culpable stone.

A year later, we were chauffeured, in our personal 1930’s American fast-backed armour-plated car with its driver’s visor-slit, to a beach-side barracks’ school at Port Dickson, commanded by the awesome figure of an ex-army major: “Drum-Tum!”

Discipline here was tough: morning lessons, interrupted only by a fresh coconut milk-and-crunchy break, were followed, after lunch, by swimming and sports on a sweeping white seemingly endless sandy beach. At one end, a small river trickled through a mangrove swamp into the azure ocean while at the other little sampans set out into the Malacca Straits from a fragrant Malay fishing kampong and returned with tiny ikan bilis and huge flat sting-rays flapping across the gunwales.

My enduring memory of this place was of being confined, in a delirium, in the doorless end bay of the barracks that was nominated the ‘sickroom,’ with its view of the coconut trees lining the land drain that bounded our property. Here I saw (as described by Charles Darwin in his Beagle record of 1836) “even a huge land crab… furnished by nature with a curious instinct and form of legs to open and feed upon the same fruit (the coconut)” advancing purposefully out of that great drain, across the few yards to the barrack’s door, and on towards my cot, ever larger, its clicking pincers agape, grinning at me.

It could climb, my delirium assured me, the leg of my little bed with ease and with equal ease split…

I was transferred to the main house and bedded on the first floor, next to the girls’ dorm for the remaining duration of my sickness, where I made my own Darwinian discovery of ‘species’ differentiation.’

(Next week: the boy from the colonies finds a place in English society)

It was the ‘Emergency’, that period when the Chinese allies that Britain had funded during WWII to hide out in the Malay jungles and attack the Japanese Imperialists invaders, turned against their benefactors and hid out in the Malay jungles and attacked the British Imperialist invaders. On the estates, ungrateful daytime ‘coolies’ became ‘bandits’ by night, slashing the trees they tended, but all the way round.

A faithful son of Empire, I returned to Great Britain to celebrate the Coronation of the young Elizabeth and join in the cheerful festivities from my high window, feasting on raw egg and ice cream. I, too, played my part, donating selflessly for the greater good, though I was never told why the Crown required my tonsils-and-adenoids.

To convalesce I was placed in a Devon boarding school to enjoy a seemingly endless quarantine after a child contracted polio there, while my parents toured the United Kingdom visiting relatives.

My reward for this sacrifice came on the return flight, in one of those new shiny state-of-the-art jet airliners, the Comet Four, for, as all the passengers slept and dreamed, I was invited to sit with the pilot in the cockpit and handle the controls as we clipped over the magical Himalayan peaks at the end of the day. Bliss. I would like to think I looked down on little Hillary and tiny Tensing waving back at me from their little peak, but sadly it could only have been that wee Jack they left behind, waving forlornly in the icy blast.

I climbed aboard one of these at Duxford air museum recently and was surprised at how it had shrunk over the years. I could barely stand up straight in the centre aisle!

Having seen the advantages of the boarding-school education at first hand, my parents packed me off, fully four and a half, to a school at the proper distance of 250 miles from a change of heart. We travelled by canvas-seated Dakota aeroplane and pencil-shaped Saracen armoured car, up and away from the sweaty jungles of my infancy to breathe the cool pure air of the Cameron Highlands. Here, again, I experienced the joy of being invited up into the ‘cockpit’ gun-turret and peer through its sights into the deepest recesses of the green jungle as my fellow passengers vomited their way to the top in the steel oven below.

My enduring memory of this school was of gazing in awe, for an instant, upon the grey-beige of my kneecap before it drowned in a flood of bright red and then at the culpable stone.

A year later, we were chauffeured, in our personal 1930’s American fast-backed armour-plated car with its driver’s visor-slit, to a beach-side barracks’ school at Port Dickson, commanded by the awesome figure of an ex-army major: “Drum-Tum!”

Discipline here was tough: morning lessons, interrupted only by a fresh coconut milk-and-crunchy break, were followed, after lunch, by swimming and sports on a sweeping white seemingly endless sandy beach. At one end, a small river trickled through a mangrove swamp into the azure ocean while at the other little sampans set out into the Malacca Straits from a fragrant Malay fishing kampong and returned with tiny ikan bilis and huge flat sting-rays flapping across the gunwales.

My enduring memory of this place was of being confined, in a delirium, in the doorless end bay of the barracks that was nominated the ‘sickroom,’ with its view of the coconut trees lining the land drain that bounded our property. Here I saw (as described by Charles Darwin in his Beagle record of 1836) “even a huge land crab… furnished by nature with a curious instinct and form of legs to open and feed upon the same fruit (the coconut)” advancing purposefully out of that great drain, across the few yards to the barrack’s door, and on towards my cot, ever larger, its clicking pincers agape, grinning at me.

It could climb, my delirium assured me, the leg of my little bed with ease and with equal ease split…

I was transferred to the main house and bedded on the first floor, next to the girls’ dorm for the remaining duration of my sickness, where I made my own Darwinian discovery of ‘species’ differentiation.’

(Next week: the boy from the colonies finds a place in English society)

Sunday, 8 February 2009

A cave, a bone, a tooth and time.

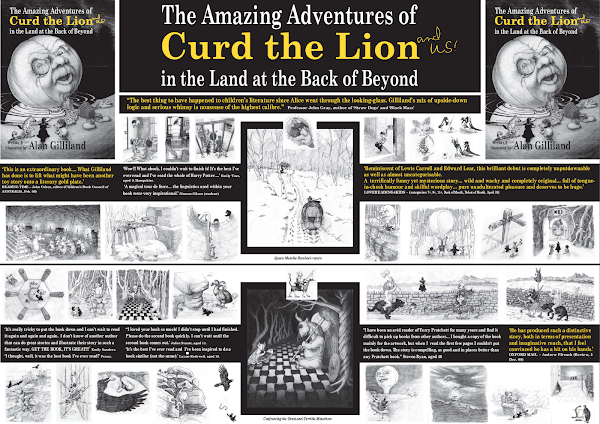

When I started out on this venture (writing my Curd the Lion book – see first post) years ago, a strangely parallel adventure befell us in real life.

I started writing and drawing the first pictures for this story of Curd the Lion and his friends, Pilgrim Crow, Sweeney the Heenie (hyena) and O’Flattery the Snake, when my fourth child, Oliver, was born.

Soon after this I took my eldest two children, Ben and Emily, on a picnic trip. Walking along the rocky bed of a half-dry stream winding through the woods, we noticed a small cliff.

Halfway up it we saw an enticing little cave with a ledge just right for a picnic. We climbed up and sat down to look at the view as we ate our sandwiches ( because children are always hungry), before exploring the cave.

The cave, we could see, went much deeper than we had expected and its lure gobbled up the sandwiches as fast as I could unwrap them.

We walked and stooped and crawled our way way into it as far as we could, discovering side tunnels and old stalactites and -mites and other bumps to bang your head and stub your toes.

Armed with my promise to return with torches and a ball of string (to find our way out again) we returned to the entrance. Scratting about in the mud looking for fossils, one of us picked up a very bone-shaped object. Picking off a little of the limestone coating we saw that it was indeed a bone.

The local museum curator confirmed that we had found, here in England, the metatarsal foot-bone of an hyena from before the last ice-age!

We were all very excited, given that Sweeney the Heenie, Curd’s rival in the story, was an hyena.

Six months later, just as I was finishing the first draft of the story, we returned, armed with hope, torches, string, trowels, a knife to scrape with and a bottle of water to rinse anything we found.

It wasn’t long before we unearthed an object that, upon scraping away the limestone coating, revealed itself to be a huge and pristine enameled tooth.

Of course, it could only be the tooth of a cave-lion just like Curd – a magical end to the story of my story-making.

We were only slightly disappointed when the Natural History Museum confirmed that BOTH foot-bone and tooth belonged to an hyena.

Only a year or two ago I discovered that our ‘secret’ cave was once famous.

Known as the ‘Hyena Cave’, discovered by quarrymen in the early 19th century, it contained a vast quantity of hyena bones, along with various other local Yorkshire creatures, such as elephants, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, bison, giant deer, small mammals and birds.

The study of these bones led eventually to a refutation of the then accepted view that the Great Flood of the Bible had either swept such creatures there (all the way from Africa) or drowned them in situ.

All the animal bones except those of the hyenas, were chewed and broken, and only partial. The cave, it appears, was a den occupied by hyenas for a very long time.

It was the cave that changed time! (from that of a consensual biblical to a scientific perception of pre-history).

Our metatarsal has since taken a walk (perhaps it’s on its way home to Yorkshire) but the great fang still keeps me company in my little shed in West Sussex.

I started writing and drawing the first pictures for this story of Curd the Lion and his friends, Pilgrim Crow, Sweeney the Heenie (hyena) and O’Flattery the Snake, when my fourth child, Oliver, was born.

Soon after this I took my eldest two children, Ben and Emily, on a picnic trip. Walking along the rocky bed of a half-dry stream winding through the woods, we noticed a small cliff.

Halfway up it we saw an enticing little cave with a ledge just right for a picnic. We climbed up and sat down to look at the view as we ate our sandwiches ( because children are always hungry), before exploring the cave.

The cave, we could see, went much deeper than we had expected and its lure gobbled up the sandwiches as fast as I could unwrap them.

We walked and stooped and crawled our way way into it as far as we could, discovering side tunnels and old stalactites and -mites and other bumps to bang your head and stub your toes.

Armed with my promise to return with torches and a ball of string (to find our way out again) we returned to the entrance. Scratting about in the mud looking for fossils, one of us picked up a very bone-shaped object. Picking off a little of the limestone coating we saw that it was indeed a bone.

The local museum curator confirmed that we had found, here in England, the metatarsal foot-bone of an hyena from before the last ice-age!

We were all very excited, given that Sweeney the Heenie, Curd’s rival in the story, was an hyena.

Six months later, just as I was finishing the first draft of the story, we returned, armed with hope, torches, string, trowels, a knife to scrape with and a bottle of water to rinse anything we found.

It wasn’t long before we unearthed an object that, upon scraping away the limestone coating, revealed itself to be a huge and pristine enameled tooth.

Of course, it could only be the tooth of a cave-lion just like Curd – a magical end to the story of my story-making.

We were only slightly disappointed when the Natural History Museum confirmed that BOTH foot-bone and tooth belonged to an hyena.

Only a year or two ago I discovered that our ‘secret’ cave was once famous.

Known as the ‘Hyena Cave’, discovered by quarrymen in the early 19th century, it contained a vast quantity of hyena bones, along with various other local Yorkshire creatures, such as elephants, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, bison, giant deer, small mammals and birds.

The study of these bones led eventually to a refutation of the then accepted view that the Great Flood of the Bible had either swept such creatures there (all the way from Africa) or drowned them in situ.

All the animal bones except those of the hyenas, were chewed and broken, and only partial. The cave, it appears, was a den occupied by hyenas for a very long time.

It was the cave that changed time! (from that of a consensual biblical to a scientific perception of pre-history).

Our metatarsal has since taken a walk (perhaps it’s on its way home to Yorkshire) but the great fang still keeps me company in my little shed in West Sussex.

Saturday, 7 February 2009

white stone

Today is marked with a white stone.

This will mean something to some people.

An incredibly nice man has offered to redesign and rebuild my website into a professionally usable and navigable site. This is not to say I do not appreciate what was done for me by another very nice man who built the original and I thank him for that.

I am finding friends and allies I could not have hoped for, not least among the animals.

At my signings I am meeting some really very nice people (I except the elderly lady who blurted loudly; ‘No, I don’t like your cover picture – AT ALL!). I hope all of you who did buy the book enjoy some it at least. Always pleased to hear if you did.

One chap today bought one at ten and returned at twelve for two more. Four bought two. (this sounds like the start of a conundrum) How many were left after four?

None.

Tomorrow. A tale about the tale (and a cave – and some bones).

This will mean something to some people.

An incredibly nice man has offered to redesign and rebuild my website into a professionally usable and navigable site. This is not to say I do not appreciate what was done for me by another very nice man who built the original and I thank him for that.

I am finding friends and allies I could not have hoped for, not least among the animals.

At my signings I am meeting some really very nice people (I except the elderly lady who blurted loudly; ‘No, I don’t like your cover picture – AT ALL!). I hope all of you who did buy the book enjoy some it at least. Always pleased to hear if you did.

One chap today bought one at ten and returned at twelve for two more. Four bought two. (this sounds like the start of a conundrum) How many were left after four?

None.

Tomorrow. A tale about the tale (and a cave – and some bones).

Friday, 23 January 2009

Wednesday, 21 January 2009

Third. A right plight.

“Nothing.” (answer to last)

Writing this blog, I feel in sympathy with Emily Dickinson’s ‘nobody’ –

“I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there's a pair of us — don't tell!

They'd banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!”

…or, as Mr. Frog ’imself might say, “dropping one’s aitches takes the ‘hauteur’ out of ‘auteur’.”

Which means I am, in my solipsism, free to write as I will.

And so, I write, on a similar theme:

The Companion.

At the lake’s edge,

A sudden gust.

Caught among the swirling

Skirts of faded petals -

Breeze of another summer -

The faint scent

Of his deep longing.

The children about his feet,

Hungry for the hundred tales

With which his life was leavened,

Are all his mind.

Courting

The trembling minstrelsy of his fingers,

A parliament of birds

Prodigiously dispute the propriety

Of each fibrous knot of memory

Discarded from the crusty fabric

Of his life - till the tale’s end

Scatters these fickle courtiers

To flock homage

Under the aegis of some other king.

.................................

©Alan Gilliland.

This may not quite be nonsense, but it is the way I am feeling today, and my imaginary companion is understanding of the vagaries of my mind.

Writing this blog, I feel in sympathy with Emily Dickinson’s ‘nobody’ –

“I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there's a pair of us — don't tell!

They'd banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!”

…or, as Mr. Frog ’imself might say, “dropping one’s aitches takes the ‘hauteur’ out of ‘auteur’.”

Which means I am, in my solipsism, free to write as I will.

And so, I write, on a similar theme:

The Companion.

At the lake’s edge,

A sudden gust.

Caught among the swirling

Skirts of faded petals -

Breeze of another summer -

The faint scent

Of his deep longing.

The children about his feet,

Hungry for the hundred tales

With which his life was leavened,

Are all his mind.

Courting

The trembling minstrelsy of his fingers,

A parliament of birds

Prodigiously dispute the propriety

Of each fibrous knot of memory

Discarded from the crusty fabric

Of his life - till the tale’s end

Scatters these fickle courtiers

To flock homage

Under the aegis of some other king.

.................................

©Alan Gilliland.

This may not quite be nonsense, but it is the way I am feeling today, and my imaginary companion is understanding of the vagaries of my mind.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)